† Corresponding author. E-mail:

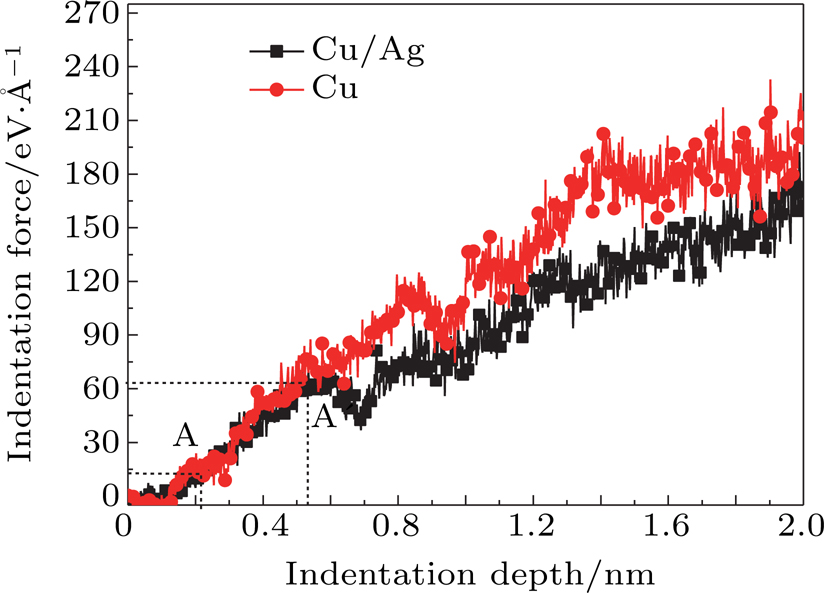

The plastic deformation mechanism of Cu/Ag multilayers is investigated by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation in a nanoindentation process. The result shows that due to the interface barrier, the dislocations pile-up at the interface and then the plastic deformation of the Ag matrix occurs due to the nucleation and emission of dislocations from the interface and the dislocation propagation through the interface. In addition, it is found that the incipient plastic deformation of Cu/Ag multilayers is postponed, compared with that of bulk single-crystal Cu. The plastic deformation of Cu/Ag multilayers is affected by the lattice mismatch more than by the difference in stacking fault energy (SFE) between Cu and Ag. The dislocation pile-up at the interface is determined by the obstruction of the mismatch dislocation network and the attraction of the image force. Furthermore, this work provides a basis for further understanding and tailoring metal multilayers with good mechanical properties, which may facilitate the design and development of multilayer materials with low cost production strategies.

The structure formed by alternately stacking two or more different metal materials is called metal multilayers. Compared with bulk pure metals, metal multilayers have high strength,[1–3] good mechanical stability,[4] strong ductility and fracture toughness.[5–8] Due to excellent performances of metal multilayers, they have been widely used in various fields.[9,10] For example, Cu/Ag multilayers are popularly used in engineering fields because of their strong antioxidative property, good electrical and thermal conductivity, and high strength.[11–13]

In order to develop metal multilayers, it is necessary to understand the plastic deformation mechanism of metal multilayers in detail. At present, there is a great deal of research about the plastic deformation mechanism of metal multilayers, such as Hall-Petch relations,[14,15] Koehler’s image force theory[16,17] and Orowan’s relation.[18] They show consistently that the plastic deformation of metal multilayers is closely related to the interface.

In our previous work, the interface effects have been investigated by theoretical models.[19–21] In addition, we also conducted a series of machining nano-material processes by MD simulation[22–24] because of its advantage in observing the deformation processes on a nanometer scale. Furthermore, MD simulation is also a viable tool to reveal the interface effect on the plastic deformation of metal multilayers, which involves the interaction between the interface and dislocations. For example, Shao and Medyanik studied the dislocation-interface interaction by MD simulation of nanoindentation in a Cu–Ni bilayer, and showed that the shear of interface results in the interfacial stacking fault formation.[25] Recently, Zhang et al. investigated the interface-dependent nanoscale frictions in Cu using MD simulation, and found that the dislocation motion was blocked by grain boundary results in the strain hardening of the bicrystals.[26] In addition, Cao et al. showed that the semi-coherent interface makes the glide dislocation difficult to cross the interface.[27] Although lots of studies have been performed to investigate the interface effect on the plastic deformation of metal materials by using MD simulation, the plastic deformation mechanism of Cu/Ag multilayers has hardly been studied on a nanoscale.

The nanoindentation experiments show that the interface plays a vital role in the plastic deformation of Cu/Ag multilayers.[28–31] However, these experiments cannot present more details about the interface effect on a nanoscale, due to the dependence on the experimental equipments such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).[32–36] Therefore, it is necessary to characterize the interface effect on the plastic deformation of Cu/Ag multilayers during nanoindentation by MD simulation.

In this paper, by using the MD simulation we conduct the nanoindentations of Cu/Ag multilayers and bulk single-crystal Cu with the use of the embedded atom method (EAM) potential function equation from Wadley et al.[37] The simulation results show the interface effect on the dislocation motion, which provides an effective basis for the analysis of the plastic deformation mechanism of Cu/Ag multilayers. The rest of this paper consists of the following parts. Firstly, the MD models and analytical methods are described in detail in the second part. The nanoindentation processes of bulk single-crystal Cu and Cu/Ag multilayers are analyzed in the third part. Finally, the plastic deformation mechanism of Cu/Ag multilayers is determined by analyzing the morphology and motion of dislocations and the indentation force curves.

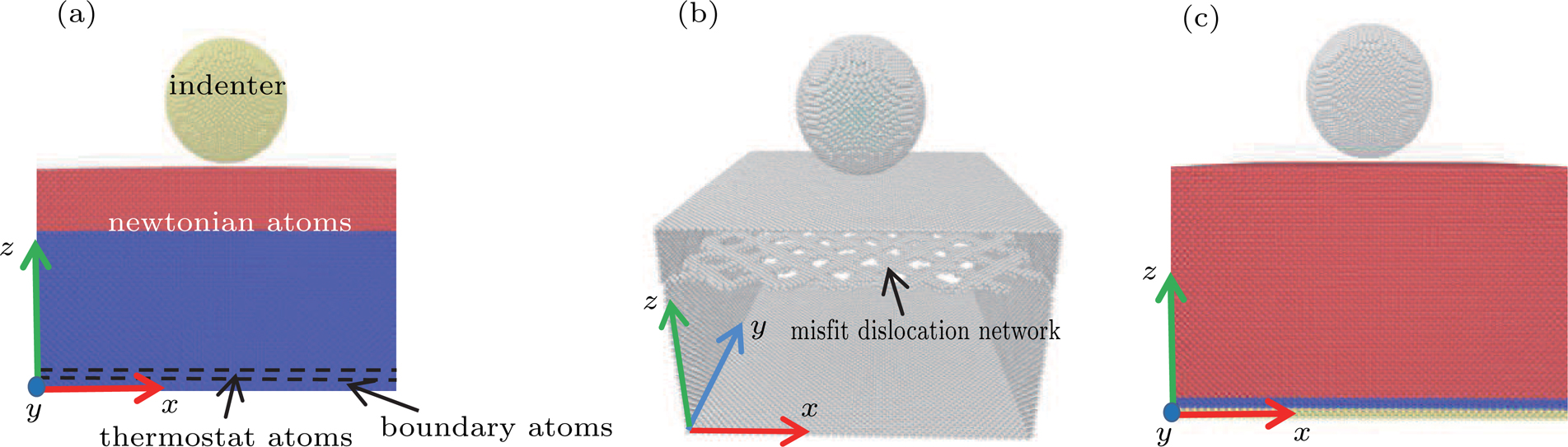

Figure

| Fig. 1. (color online) MD simulation model of (a) Cu/Ag multilayers, (b) Cu/Ag multilayers with fcc atoms hidden, and (c) bulk single-crystal Cu. |

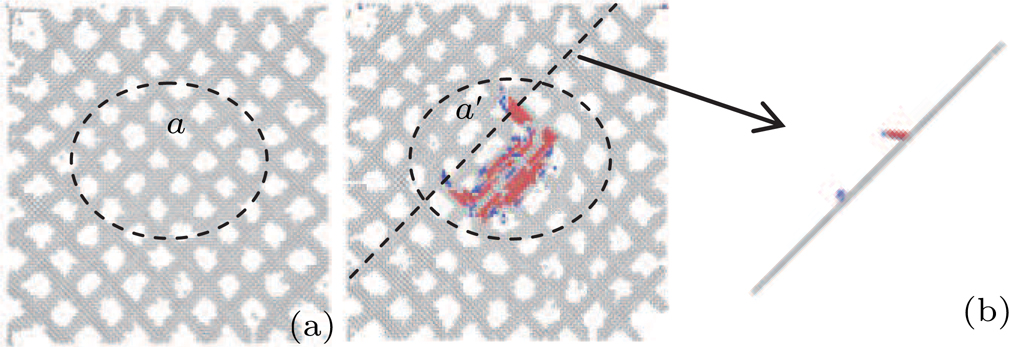

Lattice constants of fcc-Cu and fcc-Ag are 3.61 Å and 4.08 Å,[41] respectively. Therefore, their lattice mismatch is about 13%. A semi-coherent interface exists in Cu/Ag multilayers because of the lattice mismatch. Figure

The interactions between the atoms are the same in the two models, and divided into three categories. The interactions between Cu atoms and Ag atoms (Cu–Ag), between Cu atoms (Cu–Cu) and between Ag atoms (Ag–Ag) are described by the EAM potential because of its reliability.[24,41–43] The Morse potential exists between Cu atoms and diamond atoms (Cu–C).[40,44–46] There is no interaction between diamond atoms (C–C), and the indenter is seen as a rigid body because of its larger stiffness than Ag and Cu metals. Both simulation processes are composed of two stages: the relaxation stage and indentation stage. The Cu/Ag multilayers and bulk single-crystal Cu first undergo the steepest descent energy minimization at 293 K, and then are run for 100 ps under the isothermal-isobaric NVE ensemble in the relaxation stage. The two equilibrium configurations are obtained, and the equilibrium interface appears in Cu/Ag multilayers. After that, the indenter penetrates the Cu/Ag multilayers and bulk single-crystal Cu uniformly along the Z axis negative direction, respectively.

The two simulation processes are completed by the classical MD code LAMMPS, and the time step is 1 fs.[47] In order to obtain the microstructure of a certain stage of the model to facilitate the analysis of MD data, we use OVITO, a visualization tool.[48] In addition, the common neighbor analysis (CNA) method is used to effectively analyze the internal defects of the materials in the nanoindentation processes. Different types of atoms are shown in different colors. In this paper, the fcc structural atoms are in green; the hcp structural atoms are in red, which form the stacking faults; the atoms in the dislocation nucleation are shown in blue; other defective atoms and surface atoms are in white.[49]

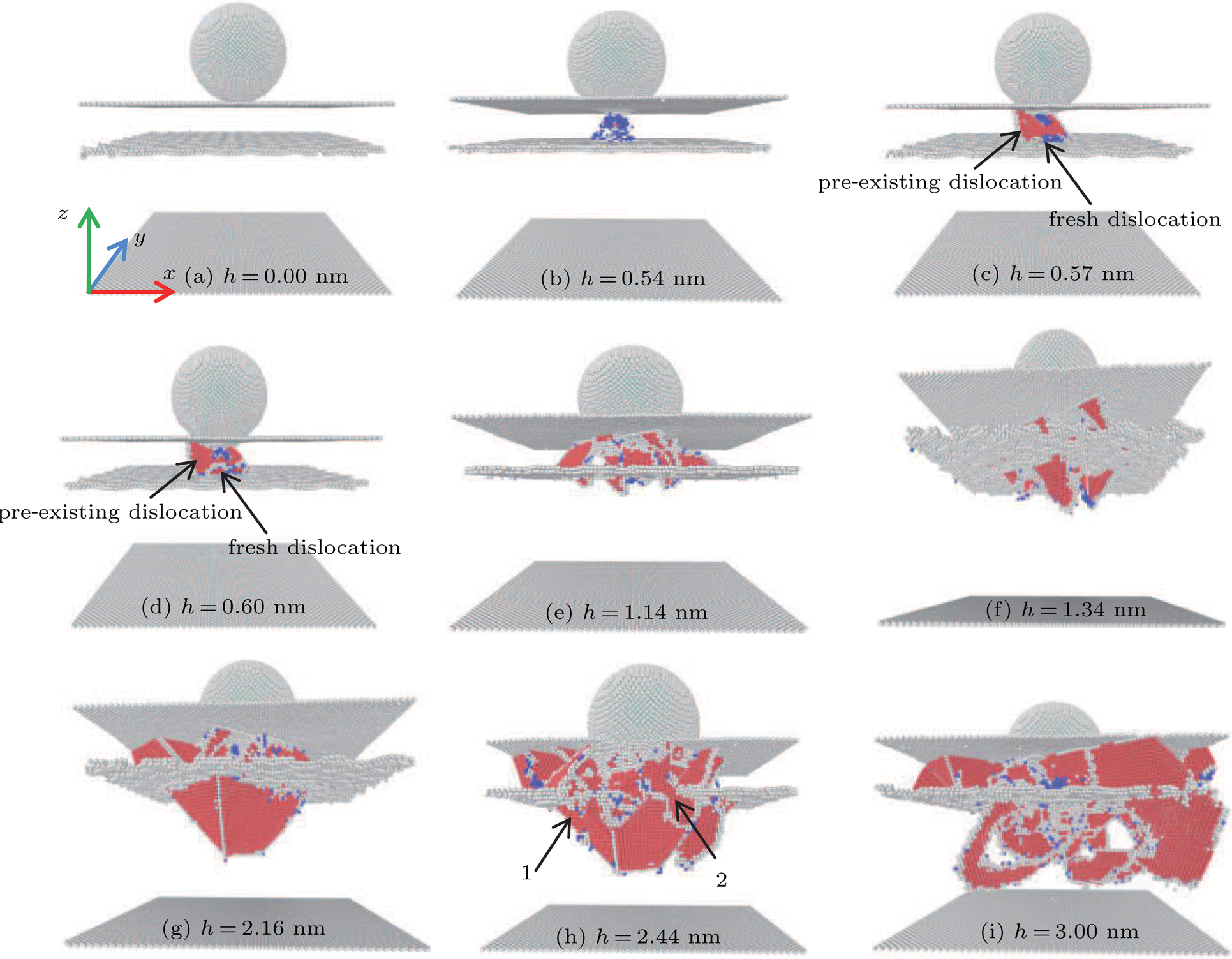

In order to reveal the plastic deformation mechanism of Cu/Ag multilayers, figures

| Fig. 2. (color online) Evolution processes of internal defects in bulk single-crystal Cu in the nanoindentation process. |

| Fig. 3. (color online) Evolution processes of internal defects in Cu/Ag multilayers in the nanoindentation process. |

Figure

Figure

With increasing indentation depth, more dislocations are emitted continuously from the top surface to the interface. figure

Figure

The SFEs of Cu, Ag and Ni

The lattice constants of fcc-Cu, fcc-Ag and fcc-Ni

Figures

Since the elastic moduli of Cu and Ag are different, there is the image force on the interface of Cu/Ag multilayers to attract or repel the dislocations. When the image force is negative, it means that the attractive force drives the dislocations through the interface, otherwise, it means that the repulsive force hinders the dislocations from crossing the interface. For Cu/Ag multilayers, the image force acting on the dislocations inside Cu nanofilm is described by the following equation:

It can be obtained from Eq. (

In summary, the three-dimensional MD simulations are conducted to investigate the plastic deformation mechanism of Cu/Ag multilayers in the nanoindentation process. Based on the above discussion, conclusions can be obtained as outlined below.

When the dislocations reach the interface, the dislocations pile-up at the interface and then the plastic deformation of the Ag matrix occurs by the nucleation and emission of dislocations from the interface and the dislocation propagation through the interface. In addition, due to the presence of the interface, the incipient plastic deformation of Cu/Ag multilayers is postponed, compared with that of bulk single-crystal Cu. The plastic deformation of Cu/Ag multilayers is affected by the lattice mismatch more than by the difference of SFE between Cu and Ag. Furthermore, the dislocation pile-up at the interface is determined by the obstruction of the mismatch dislocation network and the attraction of the image force.

It is worth noting that the nucleation and emission of dislocations from the interface and the dislocation propagation through the interface are observed during the plastic deformation of Cu/Ag multilayers. However, in the previous studies of Ni/Cu and Ni/Al multilayers, only the dislocation propagation through the interface occurs, and the nucleation and emission of dislocations from the interface are hardly observed.[25,27,54]

| [1] | |

| [2] | |

| [3] | |

| [4] | |

| [5] | |

| [6] | |

| [7] | |

| [8] | |

| [9] | |

| [10] | |

| [11] | |

| [12] | |

| [13] | |

| [14] | |

| [15] | |

| [16] | |

| [17] | |

| [18] | |

| [19] | |

| [20] | |

| [21] | |

| [22] | |

| [23] | |

| [24] | |

| [25] | |

| [26] | |

| [27] | |

| [28] | |

| [29] | |

| [30] | |

| [31] | |

| [32] | |

| [33] | |

| [34] | |

| [35] | |

| [36] | |

| [37] | |

| [38] | |

| [39] | |

| [40] | |

| [41] | |

| [42] | |

| [43] | |

| [44] | |

| [45] | |

| [46] | |

| [47] | |

| [48] | |

| [49] | |

| [50] | |

| [51] | |

| [52] | |

| [53] | |

| [54] |