†Corresponding author. E-mail: hszeng@hunnu.edu.cn

*Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11275064 and 11075050), the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education, China (Grant No. 20124306110003), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University, China (Grant No. IRT0964), and the Construct Program of the National Key Discipline, China.

From a quite general form of the Lindblad-like master equation of open two-level systems (qubits), we study the effect of Lamb shift on the non-Markovian dynamics. We find that the Lamb shift can induce a non-uniform rotation of the Bloch sphere, but that it does not affect the non-Markovianity of the open system dynamics. We determine the optimal initial-state pairs that maximize the backflow of information for the considered master equation and find an interesting phenomenon–the sudden change of the non-Markovianity. We relate the dynamics to the evolution of the Bloch sphere to help us comprehend the obtained results.

Quantum non-Markovian dynamics, due to its wide range of existence such as in the quantum optical system, [1] quantum dot, [2] superconductor system, [3] quantum chemistry, [4] biological system[5] and some possible applications such as in quantum metrology[6] and quantum key distribution, [7] has received a great deal of attention in recent years. Several suggestions[8– 13] for the measure of non-Markovianity have been presented and various dynamical properties[14– 32] of non-Markovian processes have been investigated. Experimentally, the simulation of non-Markovianity[33– 35] under controlled environments has been realized.

In the aspect of measuring the non-Markovianity of open quantum processes, Breuer, Laine, and Piilo (BLP) presented a physically intuitive method, [8] i.e., by the increase of the trace distance or distinguishability between pairs of evolving quantum states, which may be interpreted as the recovery of the lost information (the flow of the lost information from the environment back to the open system). Unfortunately, there is an optimization process in the definition, i.e., finding an optimal pair of initial states to maximize the backflow of information, which is a formidable task in practice. Though much effort has been devoted to this problem, [36– 38] it is still the main obstacle to studying non-Markovianity. In this paper, we solve this problem for a quite general non-Markovian master equation of open two-level systems. Due to the typicality of the dynamical model under consideration, the result has good applicability.

In the theoretical study of open quantum dynamics, the effect of the electromagnetic field of the environment will cause shifts of atomic energies, the very well known Lamb shift.[39, 40] For the time-independent Markovian process, the Lamb shift is a constant and thus can be removed via the renormalization of energy, i.e., by taking the Lamb shift into the transition frequencies of the open system. For non-Markovian process, however, the Lamb shift is time-dependent whose effect needs to be reexamined. The second intention of the paper is designed for this point.

In order to make our research more concrete, we start from a specific interaction model which describes a two-level system coupled to its environment via both amplitude- and phase-damping ways. In the secular approximation and the limit of weak-coupling between the open system and its environment, we derive a master equation which has a very general Lindblad-like form. We then expand our research based on this master equation. Interestingly, the results presented in this paper can be understood intuitively by relating the dynamics to the evolution of a Bloch sphere.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the origin of the general Lindblad-like non-Markovian master equation used in this paper. In Sections 3 and 4, we study respectively the effects of Lamb shift on the evolution of quantum states and on the non-Markovianity of system dynamics. In Sections 5 and 6, we discuss respectively the issues of optimal initial-state pairs and the sudden change of non-Markovianity. Finally, the conclusion is arranged in Section 7.

Consider a two-level atom with Bohr frequency ω 0 interacting with a zero-temperature bosonic reservoir modeled by an infinite chain of quantum harmonic oscillators. The total Hamiltonian for this system in the Schrö dinger picture is given by

where σ x and σ z are the Pauli operators of the atom, ω k, bk, and

The time-convolution less (TCL) projection operator technique[1] is most effective in dealing with the dynamics of open quantum systems. In the secular approximation and the limit of weak coupling between the system and its environment, by expanding the TCL generator to the second order with respect to the coupling strengths, the non-Markovian master equation describing the evolution of the open system, in the interaction picture, can be written as

where

with σ ± the inversion operators of the atom, which is the Lamb shift Hamiltonian that describes the energy shifts of the eigenstates of the two-level atom, and

describes the dissipation of the system. The Lamb shifts S± (t) of the levels | 0〉 and | 1〉 , and the time-dependent decay rate Γ (t) may be written respectively as

with ξ = {+ 1, − 1}. In the above derivation, we have used the continuum limit

The first, second, and third lines of the dissipator D[ρ (t)] describe respectively the dissipation, heating and purely dephasing of the atom to its environment. Equation (2), which may be viewed as the generalization of the Lindblad master equation, has a quite general form. In fact, many quantum dynamics of open two-level systems in the secular approximations can be cast into this form. The time-dependent decay rates and Lamb shifts may be different for different microscopic models. But our main results are in principle independent of the specific form of these expressions. It is the generality of the master equation that makes our results applicable.

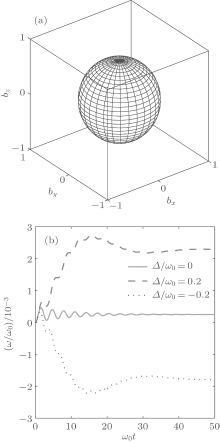

In this section, we discuss the effect of Lamb shift on the evolution of quantum states. For this purpose, we first consider the case where the Lamb shift is removed temporarily, which leads to the very simple Bloch equations

where the components of the Bloch vector are defined by bj(t) = Tr[ρ (t)σ j] with j = x, y, z. The parameters γ (t) and γ z(t) are defined by

The above Bloch equations can be solved very easily, which give the following solutions:

with

where λ is the width of the Lorentzian distribution, and we assume the Bohr frequency ω 0 = 10λ , the detuning between the atom and the central frequency of the environment Δ = 0.5λ . In the figure, we take

When the Lamb shift is considered, the Bloch equation becomes

and the evolution of bz is still given by Eq. (10). Now the evolutions of bx and by are no longer independent. The simplest way to solve this set of equations is to employ the time-dependent rotating transformation

with a time-dependent rotating angle

The component bz(t) is still given by Eq. (15).

From the above mathematical derivation, we see that the rotating transformation (19) on the one hand can tremendously simplify the process of solving the master equation (2), and on the other hand it shows the Lamb shift has a significant physical meaning: the Lamb shift induces a rotation of the Bloch sphere with respect to the z-axis. It is the use of this property that will be very convenient for future research of non-Markovian dynamics.

In fact, the above rotating effect of the Lamb shift is quite understandable based on the Bloch theory of the evolution of a two-level system.[43] When the dissipator D[ρ (t)] in Eq. (2) is ignored, the system will undergo a unitary evolution induced by Lamb shift Hamiltonian HLS(t), which up to a global phase is equivalent to the rotation transformation U(t) = exp[δ (t)σ z/2]. The inclusion of the dissipator only gives rise to the deformation (expansion and contraction) of the Bloch sphere.

We now study the effect of the Lamb shift on the non-Markovianity of the dynamical process. Among a few measures of non-Markovianity so far, the BLP measure[8] is a typical one which has physically intuitive interpretations. Note that Markovian processes always tend to continuously reduce the trace distance between quantum states, thus an increase of the trace distance during any time interval signifies the emergence of non-Markovianity. In quantum information science, the trace distance is related to the distinguishability between quantum states and its change means the exchange of quantum information between an open system and its environment. Non-Markovian processes imply the flow of the lost information from the environment to the open system.

For a given pair of initial states ρ 1, 2(0) of the system, the change of the dynamical trace distance is described by its time derivative

where ρ 1, 2(t) are the dynamical states corresponding to the initial states ρ 1, 2(0), and the trace distance is defined as D(ρ 1, ρ 2) = tr| ρ 1 − ρ 2| /2 with trace norm

as the measure of non-Markovianity of a dynamical process. In order to reflect the degrees of non-Markovianity of the whole dynamical process, the time integration is extended over all intervals in which σ is positive, and the maximum is taken over all initial-state pairs of the system. Obviously, 𝓝 = 0 for all Markovian processes. The larger the quantity 𝓝 is, the higher the non-Markovianity of the process is.

For our considered dynamics and by use of the solution of Eqs. (20) and(21) as well as Eq. (15), we obtain

where G(t) = {e− 2Θ (t)[(Δ bx)2 + (Δ by)2] + e− 2Λ (t)(Δ bz)2}− 1/2 and Δ bj = b1j(0) − b2j(0) is the difference of the initial Bloch components. It is worthwhile noting that equation (24) is independent of the Lamb shift S± (t); therefore, the Lamb shift does not affect the non-Markovianity of the system dynamics. This result is interesting but not self-evident, because the Lamb shift can affect the evolution of quantum states.

Of course, we may understand this result more easily from the picture of a Bloch sphere. As verified in the previous section, a Lamb shift only induces a rotation of the Bloch sphere, which apparently does not change the Euclidean distance in the Bloch sphere picture. In the qubit case the Euclidean distance of the Bloch vectors is up to a constant the same as the trace distance between the corresponding quantum states.[44] Therefore, the Lamb shift does not affect the non-Markovianity of quantum processes. Another intuitive interpretation may come from the observation of the BLP measure for non-Markovianity, which involves only the differences of quantum states. These differences obviously do not change under Lamb shifts, because the shifts are the same for all quantum states. So the non-Markovianity is also unchangeable.

From Eq. (24), we can easily confirm that the sufficient and necessary condition for the backflow of information is

for some time intervals [Note that G(t) is positive]. Because if one of the inequalities is satisfied, then we can always find a pair of initial states so that σ > 0. For example, if γ (t) < 0 it suffices to choose the initial states satisfying Δ bz = 0. Conversely, if σ > 0 at given time t, then at least one of the two inequalities must be satisfied.

In fact, the condition (25) is also intuitive. As mentioned in the previous section, the positivity of γ (t) and γ z(t) is the sufficient and necessary condition for the monotonous contraction of a Bloch sphere, and the contraction leads to the decrease of the Euclidean (trace) distance between quantum states, thus the positivity of γ (t) and γ z(t) is the sufficient and necessary condition of Markovian dynamics, or equivalently, equation (25) is the sufficient and necessary condition of non-Markovian dynamics.

In the calculation of a BLP measure of non-Markovianity, a key step is to find the optimal initial-state pair so that equation (23) is maximized. It is a formidable problem in practice. Here we solve this problem for the quite general non-Markovian master equation (2). Let us first intuitively analyze the problem from the picture of a Bloch sphere. It was already proved that[38] for a qubit system, the optimal initial-state pair must be located at the antipodal points of the Bloch sphere. As the increase of the trace distance corresponds to the inflation of the Bloch sphere, we then infer that the optimal initial-state pair should be such antipodal points for which the Bloch sphere oscillates most strongly in that direction, i.e., the sum of the inflations in that direction in the whole dynamical process is the largest. As the Bloch sphere governed by the master Eq. (2) is rotation symmetrical with respect to the z axis, the most strongest oscillating direction is probably either the pole direction or any direction in the equatorial plane. In other words, the optimal initial-state pair is either {| 0〉 , | 1〉 } or {| + 〉 , | − 〉 } with

Similarly, for the initial-state pair {| 0〉 , | 1〉 }, we have

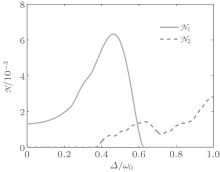

By comparing the values of 𝓝 1 and 𝓝 2, we can finally determine the optimal initial-state pair and the corresponding non-Markovianity 𝓝 = max{𝓝 1, 𝓝 2}.

The correctness of the above conjecture may be examined through concrete calculations. As the optimal initial-state pair must fit (Δ bx)2 + (Δ by)2 + (Δ bz)2 = 4, thus equation (24) may be viewed as a function of (Δ bz)2. For any fixed time t yielding σ > 0, equation (24) is maximized either at the endpoints (Δ bz)2 = 0, 4, or at (Δ bz)2 = α 0, where α 0 is a point for which the derivative of σ with respect to (Δ bz)2 vanishes. Straightforward calculation shows that there is only one extremum point

which is the minimum point of σ . Thus the maximum of σ takes place at the endpoints of (Δ bz)2 irrespective of the time t, which indicates {| 0〉 , | 1〉 } and {| + 〉 , | − 〉 } are the possible optimal initial-state pairs.

In the previous section, we provided two alternative pairs of initial states, for which the real choice for optimal initial states dependends on the structure parameters of the environment. For some parameter areas, the optimal initial-state pair may be {| + 〉 , | − 〉 } and the non-Markovianity is calculated by 𝓝 1. While for other parameter areas, the optimal initial-state pair may be {| 0〉 , | 1〉 } and the non-Markovianity is calculated by 𝓝 2. On the boundary of the two kinds of parameter areas, a sudden change of the non-Markovianity 𝓝 may take place. In order to demonstrate this point, we still take the Lorentzian density of Eq. (16) as an example and plot the non-Markovianity as a function of the dimensionless detuning as in Fig. 2, where we take λ = 0.1ω 0,

It is worthwhile stressing that the sudden change of non-Markovianity in this model is related closely to the rotation symmetry of the Bloch sphere with respect to the z axis. It is the rotation symmetry that makes the optimal initial-state pairs either along the z axis or in the equatorial plane. Thus if you change the parameters of the dynamics, eventually you will find ones for which the optimal initial-state pair jumps from the z axis to the equatorial plane or vice versa unless the optimal initial-state pair is unique.

In conclusion, by considering a specific interaction model that describes a two-level system coupling to a zero-temperature structured environment via amplitude-phase dampings, in the limit of weak coupling between the system and its reservoir and by use of the secular approximation, we derived a non-Markovian master equation for the reduced state of the open system which has a quite general Lindblad-like form. Based on this, we found on the one hand that the time-dependent Lamb shift can induce a non-uniform rotation of the Bloch sphere and thus alter the evolution of quantum states. Therefore, in quantum information processing, the Lamb shift should be taken into consideration. On the other hand however, it does not affect the non-Markovianity of the open system dynamics and thus can be removed from the master equation.

We also, for the general non-Markovian master equation, obtained the sufficient and necessary conditions for the backflow of information, and found the optimal initial-state pairs that maximize the backflow of information. There are two alternative initial-state pairs depending on the environmental structure parameters, the polar or the equatorial state pair, for the calculation of non-Markovianity. The change of the optimal initial-state pairs can lead to the sudden change of non-Markovianity.

One key factor in our study is the use of the rotating transformation which not only tremendously simplifies the solving process of the master equation, but also reveals the significant physical meaning of the Lamb shift, i.e., the Lamb shift induces a rotation of the Bloch sphere with respect to the z axis, which establishes the foundation of our research work. Almost all of the results listed in this paper can be explained intuitively from the rotation and the symmetry under the rotation.

Though the discussion was started from a specific interaction model that describes amplitude-phase dampings of a two-level open system, the results have good applicability. Because on the one hand the derived Lindblad-like master equation has a quite general form, and on the other hand the results in principle do not depend on specific environmental structures. We believe our results are very helpful for the study of non-Markovian dynamics.

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

|

| 42 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

|