† Corresponding author. E-mail:

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11374081 and 11004044), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (Grant Nos. N150905001, L1509006, and N140901001), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowships for Foreign Researchers (Grant No. P10060), and the Alexander von Humboldt (AvH) Foundation (Research stipend to L. Li).

The magnetocaloric effect (MCE) in many rare earth (RE) based intermetallic compounds has been extensively investigated during the last two decades, not only due to their potential applications for magnetic refrigeration but also for better understanding of the fundamental problems of the materials. This paper reviews our recent progress on studying the magnetic properties and MCE in some binary or ternary intermetallic compounds of RE with low boiling point metal(s) (Zn, Mg, and Cd). Some of them exhibit promising MCE properties, which make them attractive for low temperature magnetic refrigeration. Characteristics of the magnetic transition, origin of large MCE, as well as the potential application of these compounds are thoroughly discussed. Additionally, a brief review of the magnetic and magnetocaloric properties in the quaternary rare earth nickel boroncarbides RENi2B2C superconductors is also presented.

The magnetocaloric effect (MCE) is a magneto-thermodynamic phenomenon, which was first discovered in pure Fe by Emil Warburg in 1881,[1] and its origin was independently explained by Debye and Giauque in the 1920s.[2,3] All magnetic materials exhibit MCE, although the intensity of this effect depends on the properties of each material. Generally, for a simple ferromagnetic material near its Curie temperature, when a magnetic field is applied, the spins tend to align parallel to the magnetic field, which lowers the magnetic entropy. To compensate for the loss in the magnetic entropy in an adiabatic (isentropic) process, the temperature of the material increases. When the magnetic field is removed, the spins tend to become random which increases the magnetic entropy and the material cools. Meanwhile, Debye and Giauque have also proposed the adiabatic demagnetization in order to achieve temperature lower than that of the liquid helium. This possibility was later experimentally demonstrated by the chemist Nobel Laureate William F. Giauque in 1933, he was able to reach a temperature of 0.25 K based on the adiabatic demagnetization of 61 g paramagnetic salt Gd2(SO4)3· 8H2O.[4] Besides the success in the ultralow temperature, the magnetic refrigeration technology has also been applied at the higher temperature ranges, such as ∼ 2 K to 20 K, the range of liquid helium and hydrogen, as well as ∼ 20 K to 80 K, the range of liquid hydrogen and nitrogen.[5–8]

In 1997, two key developments enhanced the feasibility for producing a magnetic refrigerator for commercial or industrial use. The first is that Zimm et al.[9] realized the first near room temperature magnetic refrigeration prototype at the Ames Laboratory. The second is that Pecharsky and Gschneider[10] observed a giant MCE in the Gd5(Si2Ge2) compound. Besides the discovery of the giant MCE in Gd5(Si2Ge2) and related compounds,[10,11] a number of materials with giant/large MCE have been realized in the last three decades, for example, RECo2 (RE = Er, Ho, and Dy) alloys,[12,13] MnAs based compounds,[14–17] manganites (RE, M)MnO3, (RE = lanthanide, M = Ca, Sr, and Ba),[18,19] Ni–Mn–X (X = Ga, In, and Sn) based Heusler alloys,[20–24] La(Fe,Si)13 and related compounds,[25–28] MnTX (T = Co, Ni, and Fe; X = Si, Ge) based compounds,[29–32] as well as some rare earth based intermetallic compounds.[33–36] The structure, physical properties, as well as the MCE and its application in most of the above mentioned materials have been summarized in a number of review articles,[11–14,17–19,22,23,26,27,32–35,37–40] which will not be repeated here. In this paper, we give a brief review of our recent progress in exploring magnetocaloric materials, mainly related to several typical systems of RE-based intermetallic compounds.

The MCE is an intrinsic phenomenon for a magnetic material, which manifests as the isothermal magnetic entropy change ΔSM or/and the adiabatic temperature change ΔTad when it is exposed to a varying magnetic field, the definition of ΔSM and ΔTad can be found in Fig.

The temperature dependence of total entropy S under different fields can be calculated from the heat capacity by numerical integration

According to the thermodynamical theory, the isothermal magnetic entropy change associated with a magnetic field variation is given by

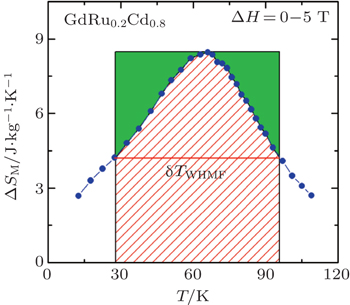

Another important quality factor(s) for magnetocaloric materials is the relative cooling power (RCP) or/and refrigerant capacity (RC), which is a measurement of the amount of heat transfer between the cold and hot reservoirs in an ideal refrigeration cycle. The RCP is defined as the product of the maximum magnetic entropy change

An example for the evaluation of the RCP and RC is displayed in Fig.

It is well known that the magnitude, temperature, and magnetic field change dependence of MCE have strong correlations with the nature of the corresponding magnetic phase transition; therefore, it is important to determine the order of magnetic transition of the magnetocaloric materials. The Inoue–Shimizu model,[41,42] which involves a Landau expansion of the magnetic free energy up to the sixth power of the total magnetization M, can be used to determine the magnetic transition type,[41,42]

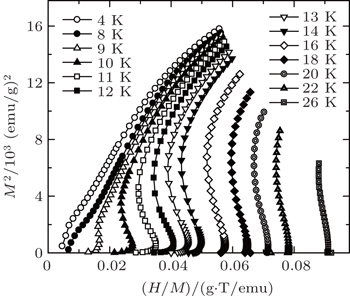

The parameters c1(T), c2(T), and c3(T) represent the Laudau coefficients, and it has been reported that the order of a magnetic transition is related to the sign of c2(T). A transition is expected to be the first order when c2(∼ TC) is negative, whereas it will be the second order for a positive c2(∼ TC). The sign of c2 can be determined by the Arrott plot (H/M versus M2 curves),[43] i.e., the magnetic transition is of the second order if all the H/M versus M2 curves have positive slopes. On the other hand, if the H/M versus M2 curves show negative slopes, the magnetic transition is of the first order. In the present review, the order of magnetic phase transition of all the materials was determined by this method.

The rare earth (RE) and transition metal (T) based systems have been intensively investigated in recent years with respect to their interesting chemical and physical properties as well as practical applications in a wide spectrum of industries. Depending on the constituent element and composition, various properties like magnetic ordering, superconductivity, heavy-fermion behavior, valence fluctuation, large magneto-resistance (MR) effect, and large/giant MCE have been observed.[44–48] Compared to the other transition metals, Zn, Mg, and Cd-based intermetallic compounds are less researched. This might be a consequence of the difficulty in material synthesis due to the low boiling point (high vapour pressure) of Zn, Mg, and Cd. Pöttgen et al.[49,50] have proposed a simple method to prepare such materials. First, stoichiometric amounts (0.5%–1% of the low boiling point metals were added) of the consistent elementals with purity better than 99.9% were weighted. Second, the weighted metals were arc-welded[49] in a Ta or Nb tube under an argon pressure of ca. 75–85 kPa. The argon was purified over a titanium sponge (900 K), silica gel, and molecular sieves. Third, the crucible was placed in a water-cooled sample chamber of an induction furnace (Hüttinger Elektronik, Freiburg, Germany, Typ TIG 1.5/300)[50] and heated up to a certain high temperature for several minutes, followed by several hours annealing at a selected temperature. Then the obtained samples were ground and cold-pressed into pellets, and finally annealed at a certain temperature for several days in evacuated quartz tubes. The structural properties and phase purity were subsequently characterized by x-ray powder diffraction (XRD) and energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analyses. In the following sections, our recent progress related to the magnetism and MCE in the binary or ternary intermetallic compounds of RE with low boiling point metal(s) (Zn, Mg, and Cd) is reviewed, respectively. For a quick comparison, the magnetic transition temperatures together with the MCE parameters of the compounds in the present review as well as some other rare earth based intermetallic compounds with significant MCE properties are summarized in Table

| Table 1. The transition temperature (TM), the maximum magnetic entropy change |

The equiatomic binary compounds REZn with the cubic CsCl-type structure (space group Pm3m) have attracted some attention due to their simple crystal structure as well as their interesting physical and chemical properties.[51–54] The magnetic studies revealed that the heavy REZn compounds order ferromagnetically with the ordering temperature ranging from 267 K for GdZn to 8.5 K for TmZn, whereas the light ones order antiferromagnetically.[51–54] Sousa et al.[55,56] have theoretically investigated the MCE in REZn (RE = Tb, Ho, and Er), and some anomalies in ΔSM(T) curves were found due to spontaneous and/or spin reorientation transitions in these compounds. Very recently, we have experimentally investigated the magnetic phase transition and magnetocaloric properties of REZn (RE = Tm and Ho) compounds.[57,58]

Figure

| Fig. 3. Temperature dependence of the zero field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling (FC) magnetization (M) for TmZn under various magnetic fields (H) up to 1 T.[57] |

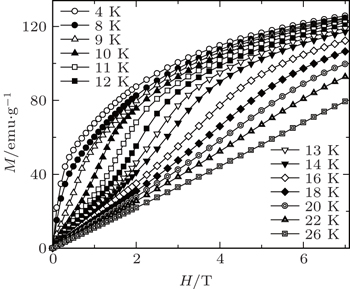

| Fig. 4. Magnetic field dependence of the magnetization (increasing field only) for TmZn at some selected temperatures.[57] |

| Fig. 5. The plots of H/M versus M2 for TmZn at some selected temperatures.[57] |

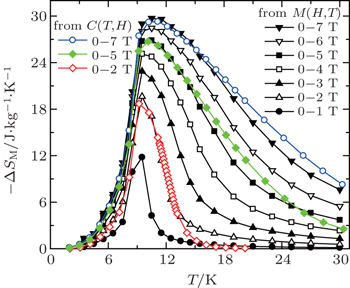

The temperature dependences of −ΔSM and ΔTad for TmZn are shown in Figs.

| Fig. 6. Temperature dependence of magnetic entropy change −ΔSM for TmZn with the magnetic field changes up to 0–7 T.[57] |

| Fig. 7. Temperature dependence of adiabatic temperature change ΔTad for TmZn with the magnetic field changes up to 0–7 T.[57] |

Whereas, two successive magnetic transitions are observed around TC ∼ 72 K and TSR ∼ 26 K for HoZn, which are the paramagnetic to ferromagnetic and the spin reorientation transitions, respectively.[58] Magnetization and modified Arrott plots indicate that HoZn undergoes a second-order magnetic phase transition around TC. The critical behavior around TC has been investigated by modified Arrott plots, scaling analysis, scaling plots, and field change dependence on the magnetic entropy change method. The critical exponents β, γ, and δ of HoZn are determined to be 0.47 ± 0.02, 1.09 ± 0.03, and 3.32 ± 0.04, respectively, which have some small deviations from the mean-field theory, indicating a short range or a local magnetic interaction which is properly related to the coexistence of FM and SR transitions at low temperature.[58]

The magnetic entropy change ΔSM for HoZn was calculated from the M(H, T) data (as shown in Fig.

| Fig. 8. Magnetic entropy change −ΔSM as a function of temperature for various magnetic field changes up to 0–7 T for HoZn.[58] |

Hermes et al.[59] have studied the magnetic properties and MCE in EuRh1.2Zn0.8, which crystallizes with the MgCu2 structure and orders ferromagnetically at TC ∼ 95 K. For the magnetic changes of 0–2 T and 0–5 T, the values of

The ternary RE-rich intermetallic compounds of the general composition RE4TMg (T = Rh, Pd, and Pt), crystallizing in the cubic Gd4RhIn-type structure, have attracted some attention due to their interesting physical and chemical properties.[62–65] For this type of crystal structure, there are three crystallographically independent RE sites and the rare structural motif of Mg4 tetrahedra. The transition metal atoms are located in RE6 trigonal prisms with strong covalent RE–T bonding. These RE6T basic building units are condensed via common corners and edges to a three-dimensional network in which the cavities are filled by the Mg4 tetrahedra. Recently, we have reported the magnetic properties and MCE of RE4PdMg (RE = Eu and Er) and RE4PtMg (RE = Ho and Er).[66–68] The magnetic phase transition, the origin of the MCE, and its potential application for magnetic refrigeration of these compounds will be shown below.

Figure

| Fig. 9. (a) Temperature dependence of zero field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling (FC) magnetization M (left scale) as well as dMFC/dT (right scale) for Eu4PdMg in an external magnetic field H = 0.1 T. (b) Temperature dependence of FC magnetization M (left scale) and dMFC/dT (right scale) for Eu4PdMg under H = 1 T.[66] |

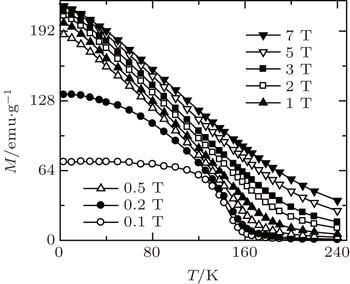

| Fig. 10. Temperature dependence of the magnetization for Eu4PdMg under various magnetic fields up to 7 T.[66] |

A set of magnetic isotherms were measured for Eu4PdMg in the temperature range from 3 K to 220 K to evaluate its magnetic entropy change. No obvious hysteresis can be observed in this temperature range. Additionally, the order of magnetic phase transition in Eu4PdMg is confirmed to be the second order based on the Banerjee criterion. The resulted −ΔSM(T) curves with the magnetic field changes up to 0–7 T are shown in Fig.

| Fig. 11. Temperature dependence of magnetic entropy change −ΔSM for Eu4PdMg with the magnetic field changes up to 0–7 T.[66] |

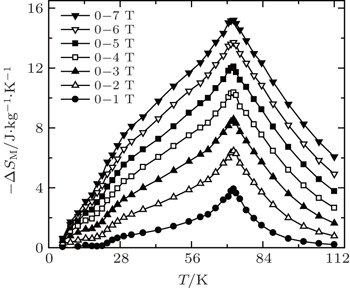

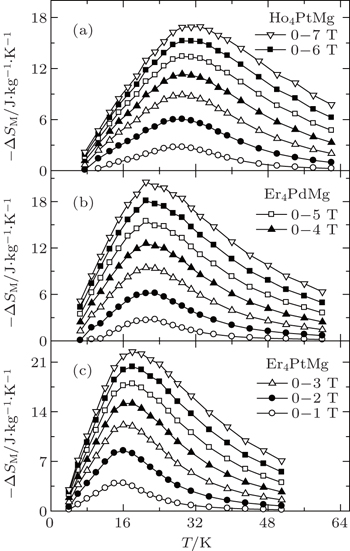

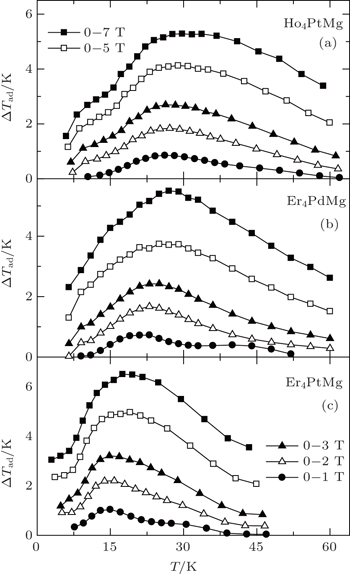

Very recently, the magnetic properties and MCE in Ho4PtMg, Er4PdMg, and Er4PtMg compounds have been investigated by magnetization and heat capacity measurements.[67,68] The compounds Ho4PtMg, Er4PtMg, and Er4PdMg undergo a second order magnetic phase transition from PM to FM at the Curie temperatures of 28 K, 21 K, and 16 K, respectively. The resulting temperature dependence of −ΔSM and ΔTad with various magnetic field changes up to 0–7 T for Ho4PtMg, Er4PdMg, and Er4PtMg are shown in Figs.

| Fig. 12. Temperature dependence of magnetic entropy change −ΔSM with the magnetic field changes up to 0–7 T for (a) Ho4PtMg, (b) Er4PdMg, and (c) Er4PtMg.[67,68] |

| Fig. 13. Temperature dependence of adiabatic temperature change ΔTad with the magnetic field changes up to 0–7 T for (a) Ho4PtMg, (b) Er4PdMg, and (c) Er4PtMg.[67,68] |

Linsinger et al.[69] have studied the magnetism and MCE in the Gd2NixCu2−xMg (x = 1 and 0.5) compounds. Both compounds show a large reversible MCE near their ordering temperatures. The values of

Due to the high toxicity of Cd and its compounds, the Cd-based alloys and compounds have limited technical application, and there is little work on the related topics.[71–73] Hermes et al.[72] have investigated the magnetic and MCE properties in the Er4NiCd compound which crystallizes in the Gd4RhIn type structure. They found that Er4NiCd shows a Curie–Weiss behavior above 50 K with TN = 5.9 K. Under a field of 0.4 T, a metamagnetic step is visible, which together with the positive paramagnetic Curie-temperature (7.5 K) indicates a rather unstable antiferromagnetic ground state. The values of

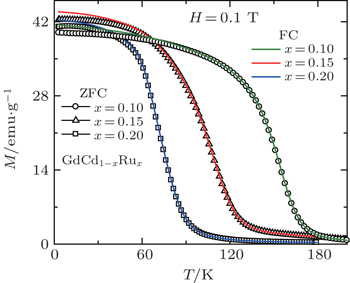

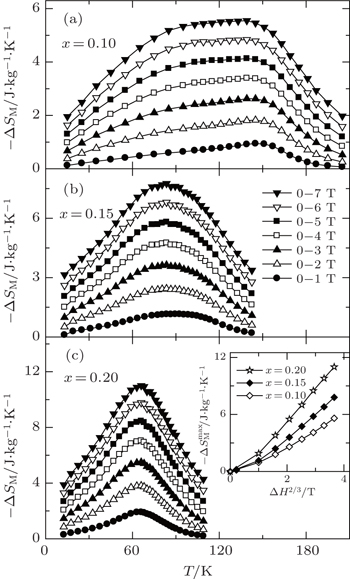

Recently, Li et al.[73] have investigated the magnetism and MCE in GdCd1−xRux (x = 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2) solid solutions. Figure

| Fig. 14. Temperature dependence of zero field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling (FC) magnetization M for GdCd1−xRux (x = 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2) under a low magnetic field of H = 0.1 T.[73] |

| Fig. 15. Temperature dependence of magnetic entropy change −ΔSM with various magnetic field changes for GdCd1−xRux (x = 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2). The inset shows the maximum magnetic entropy change  |

The

The quaternary rare earth nickel boroncarbides RENi2B2C, which crystallize in the tetragonal LuNi2B2C-type structure, have attracted a great deal of attention due to the coexistence of superconductivity and magnetic ordering phenomena.[99–103] The compounds are long range magnetic ordered for RE = Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, and Tm. The superconductivity is observed for RE = Y, Lu, Dy, Ho, Er, and Tm. Thus, superconductivity coexists with magnetic order for RE = Dy, Ho, Er, and Tm, and the ratio of superconducting transition temperature TSC to antiferromagnetic (AF) ordering temperature TN ranges from TSC/TN = 7.0 for TmNi2B2C to 0.60 for DyNi2B2C.[101–103] The coexistence and competition of magnetism and superconductivity in these compounds have been systematically investigated experimentally and theoretically.[99–103] In recent years, we have further investigated the MCE in parent and doped RENi2B2C superconductors.[104–107] The main achievements will be shown in the following sections. The superconducting transition and the magnetic ordering temperatures together with the MCE parameters are summarized in Table 2 for a quick comparison of the MCE in the RENi2B2C superconductors.

| Table 2. The superconductivity transition temperature (TSC), the magnetic transition temperature (TM), the maximum values of magnetocaloric parameters ( |

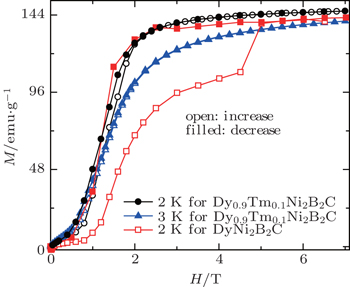

Figure

| Fig. 16. Magnetic isothermals on increasing (open symbols) and decreasing (filled symbols) field for Dy0.9Tm0.1Ni2B2C at 2 K and 3 K as well for DyNi2B2C at 2 K.[104] |

The resulted magnetic entropy changes −ΔSM in Dy0.9Tm0.1Ni2B2C, which were calculated from M(H, T) curves as a function of temperature, are shown in Fig.

| Fig. 17. Temperature dependence of magnetic entropy change −ΔSM for Dy0.9Tm0.1Ni2B2C. The inset shows the maximum magnetic entropy change  |

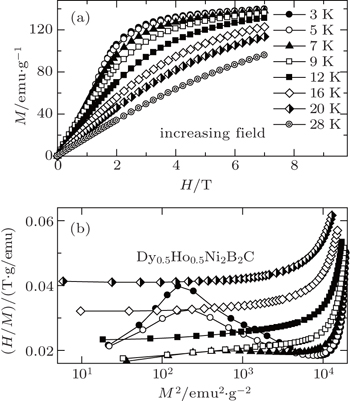

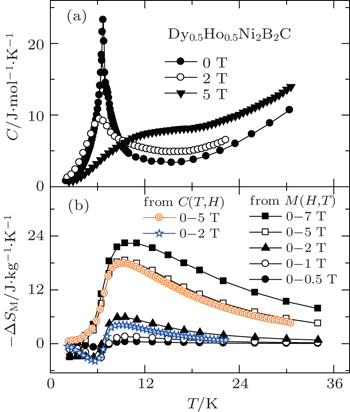

We have also investigated the superconductivity, magnetic properties, and MCE in Dy1−xHoxNi2B2C (x = 0–1) superconductors. The superconducting transition temperature TSC and the magnetic ordering temperature TM are determined to be 6.4 K, 6.4 K, 6.2 K, 8.1 K, 8.2 K and 10 K, 8.5 K, 8 K, 6 K, 5 K for x = 0, 03, 0.5, 0.7, 1, respectively.[105,106] A set of selected magnetic isothermals on increasing and decreasing field for Dy1−xHoxNi2B2C (x = 0, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 1) are measured in the temperature range from 2 K to 36 K up to 7 T. Although some hysteresis of M(H) can be observed at low temperatures, it gradually becomes smaller with increasing temperature, and almost disappears above 5 K. All the samples show similar behaviors. Several isotherms with increasing field for x = 0.5 are presented in Fig.

| Fig. 18. (a) Magnetic field dependence of the magnetization for Dy0.5Ho0.5Ni2B2C at some selected temperatures. (b) The plots of H/M versus M2 for Dy0.5Ho0.5Ni2B2C at some selected temperatures. Copyright (2011) The Japan Society of Applied Physics.[105] |

The magnetic entropy change −ΔSM was calculated from magnetization isotherm M(H,T) curves. The resulted temperature dependence of −ΔSM is shown in Fig.

| Fig. 19. Temperature dependence of magnetic entropy change −ΔSM calculated from M(T,H) for Dy1−xHoxNi2B2C (x = 0, 0.3, 0.7, and 1). Copyright (2011) The Japan Society of Applied Physics.[105] |

| Fig. 20. (a) Temperature dependence of heat capacity under the magnetic field of 0 T, 2 T, and 5 T for Dy0.5Ho0.5Ni2B2C. (b) Temperature dependence of magnetic entropy change −ΔSM for Dy0.5Ho0.5Ni2B2C calculated from C(T,H) and M(T,H) respectively. Copyright (2011) The Japan Society of Applied Physics.[105] |

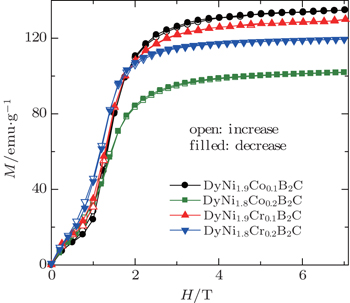

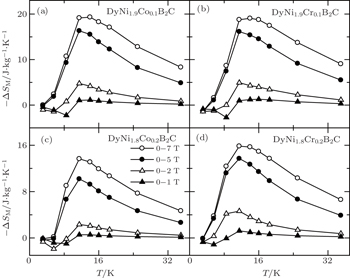

The magnetic properties and MCE of the DyNi2−xAxB2C (A = Co and Cr, x = 0.1 and 0.2) compounds were also investigated. No superconductivity can be observed above 2 K, and the magnetic transition temperatures TM are determined to be 9.8 K, 8.4 K, 8.0 K, 9.2 K, and 8.8 K for x = 0, 0.1 (Co), 0.2 (Co), 0.1 (Cr), and 0.2 (Cr) in DyNi2−xAxB2C system, respectively. Figure

| Fig. 21. Magnetic isothermals on increasing (open symbols) and decreasing (filled symbols) field at 2 K for DyNi2−xAxB2C (A = Co and Cr, x = 0.1 and 0.2).[107] |

To evaluate the MCE in DyNi2−xAxB2C (A = Co and Cr, x = 0.1 and 0.2), a set of magnetic isothermals were measured. All the samples show similar behaviors. Several isotherms of DyNi1.8A0.2B2C for A = Co and Cr are presented in Figs.

| Fig. 22. Magnetic isothermals at some selected temperatures for (a) DyNi1.8Co0.2B2C and (b) DyNi1.8Cr0.2B2C. The curves of H/M versus M2 for (c) DyNi1.8Co0.2B2C and (d) DyNi1.8Cr0.2B2C at some selected temperatures.[107] |

The temperature and field dependences −ΔSM for DyNi2−xAxB2C (A = Co and Cr, x = 0.1 and 0.2) were calculated based on the M(H,T) curves (as shown in Fig.

| Fig. 23. Temperature dependence of magnetic entropy change −ΔSM for DyNi2−xAxB2C (A = Co and Cr, x = 0.1 and 0.2).[107] |

Zhang and Yang[108] have investigated the magnetic properties and MCE in ErNi2−xFexB2C (x = 0, 0.1, and 0.2) compounds. Similar to those of DyNi2−xAxB2C (A = Co and Cr, x = 0.1 and 0.2), substitution of Fe for Ni lowers the magnetic transition temperature TM, and reduces the magnetic hysteresis of ErNi2B2C. The inverse MCE under low magnetic field at low temperatures is attributed to the nature of antiferromagnetic state for the present ErNi2−xFexB2C compounds. A normal MCE is observed under higher magnetic field changes, which is related to a field-induced first order metamagnetic transition from AFM to FM state. For the magnetic field change of 0–7 T, the maximum values of magnetic entropy change

Investigations of MCE are of great interest for fundamental research and technological application. Our recent progress of the magnetic properties and MCE as well as its origin and potential application for magnetic refrigeration in some rare earth based intermetallic compounds are reviewed, and some of them possess excellent MCE properties. The main achievements are summarized as follows. 1) The TmZn compound exhibits a ferromagnetic state below the Curie temperature of TC = 8.4 K, and processes a field-induced metamagnetic phase transition around and above TC, resulting in a giant reversible MCE. Particularly, the values of

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | |

| 23 | |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | |

| 30 | |

| 31 | |

| 32 | |

| 33 | |

| 34 | |

| 35 | |

| 36 | |

| 37 | |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | |

| 42 | |

| 43 | |

| 44 | |

| 45 | |

| 46 | |

| 47 | |

| 48 | |

| 49 | |

| 50 | |

| 51 | |

| 52 | |

| 53 | |

| 54 | |

| 55 | |

| 56 | |

| 57 | |

| 58 | |

| 59 | |

| 60 | |

| 61 | |

| 62 | |

| 63 | |

| 64 | |

| 65 | |

| 66 | |

| 67 | |

| 68 | |

| 69 | |

| 70 | |

| 71 | |

| 72 | |

| 73 | |

| 74 | |

| 75 | |

| 76 | |

| 77 | |

| 78 | |

| 79 | |

| 80 | |

| 81 | |

| 82 | |

| 83 | |

| 84 | |

| 85 | |

| 86 | |

| 87 | |

| 88 | |

| 89 | |

| 90 | |

| 91 | |

| 92 | |

| 93 | |

| 94 | |

| 95 | |

| 96 | |

| 97 | |

| 98 | |

| 99 | |

| 100 | |

| 101 | |

| 102 | |

| 103 | |

| 104 | |

| 105 | |

| 106 | |

| 107 | |

| 108 |